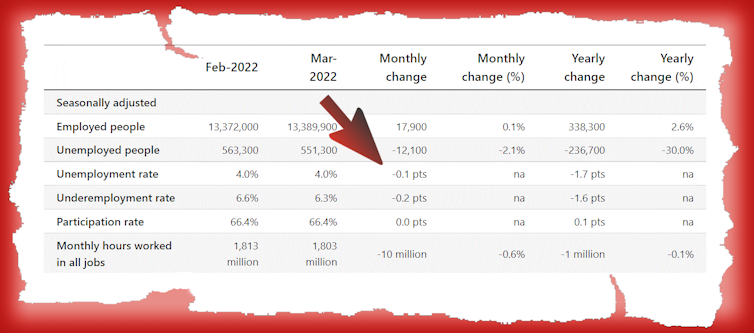

The official employment figures say the unemployment rate for March was 4.0%, exactly the same as a month earlier.

But if you’re prepared to download the spreadsheet and work it out, you’ll find that expressed to two decimal places the rate actually fell, from 4.04% to 3.95%.

The Bureau of Statistics confirms this by saying on its website that the unemployment rate fell by 0.1 percentage points between February and March while also (apparently inconsistently) saying it was 4.0% in both months.

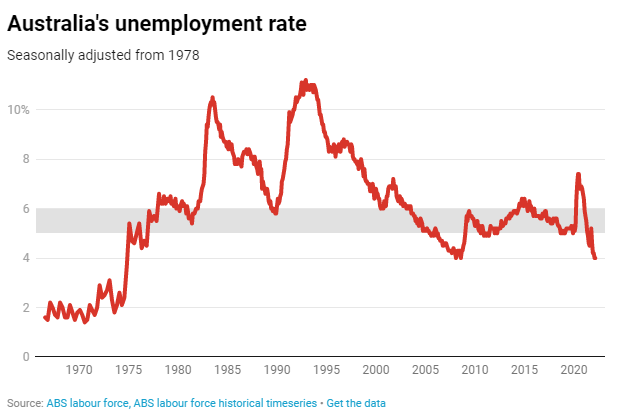

This result, clearly below 4%, is the lowest rate of unemployment Australia has seen since the monthly series of labour force statistics began in February 1978, and the lowest since the November quarter of 1974, almost 50 years ago, when the figures were quarterly.

Top Australian Brokers

- Pepperstone - Trading education - Read our review

- IC Markets - Experienced and highly regulated - Read our review

- eToro - Social and copy trading platform - Read our review

After the decade up to March 2020 in which the rate hardly moved above 6% or below 5%, the new rate of 3.95% is an enormous step in the right direction.

But we need to worry about more than unemployment. Workers can be underemployed (getting less hours than they would like) and people who would like to work but think they won’t get work, may stop searching and not get recorded as unemployed.

There’s good news on both counts.

Less underemployment, fewer hidden unemployed

The proportion of workers underemployed has fallen from 9.3% prior to COVID in March 2020 to 6.6%. And rather than people withdrawing from the labour force and not looking for work, the rate at which people are either working or looking is up half a percentage point on before COVID.

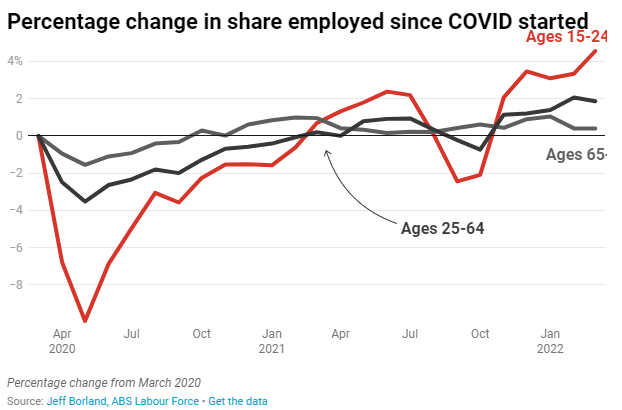

As well, in an instance of the adage that a rising tide lifts all boats, young Australians who in the 2010s lost out as the economy slowed, now seem to be benefiting most from the pick-up.

The proportion of young Australians who are employed is an extraordinary 4.6 percentage points higher than in March 2020.

This compares with an improvement of 1.9 percentage points for Australians aged 25 to 64 years, and 0.4 percentage point for Australians aged 65 years and over.

A rate of unemployment below 4% is certainly a positive. It means more of the nation’s productive resources are being used. It has improved the living standards of the 170,000 people employed today who would have not been, had unemployment remained where it was before COVID.

But those benefits will only stay in place as long as unemployment remains low. Our objective ought to be to keep it as low as possible for as long as possible.

How can we keep unemployment below 4%?

Unemployment fell below 4% because more of the population found work.

The economic stimulus the government provided to respond to COVID was built for a worst case that didn’t materialise – people generally kept their jobs. As a result it added to employment growth, and established that it was easier to get unemployment down than had been generally realised.

This suggests that keeping unemployment below 4% will depend on being committed to that goal.

Much of the COVID stimulus has been saved and has yet to make its way into spending. This, and the new spending measures in the 2022 budget, are likely to maintain the impetus needed to keep unemployment low for the months ahead.

Beyond that, what happens to unemployment will depend on the next government’s decisions.

That 1.3 million extra jobs pledge

All this must mean the Coalition’s pledge to create 1.3 million extra jobs in the next five years is what’s needed. Well, maybe.

Certainly, employment has to grow for the rate of unemployment to stay low. But the absolute number of jobs only has relevance for the rate of unemployment when we also know what is happening to the number of people who want to work.

Depending on whether the keenness of Australians to get jobs (participation) increases at a faster or slower rate than employment, 1.3 million extra jobs could either cut the rate of unemployment or be insufficient to stop it climbing.

Suppose 1.3 million jobs are created in the next five years as the Coalition has pledged, and all of them increase employment. And suppose also that the working age population and labour force participation rate grow at the same pace as for the past five years.

Then Australia’s rate of unemployment in five years time will be about 4.4%, which is higher rather than lower than it is today.

Ultimately what we care about is the proportion of the population that is in work, rather than the number of jobs created, which can be related to population.

A more meaningful pledge would be to keep unemployment at the lowest possible rate below 4% without causing excessive wage inflation.