Unlike many airlines, Australia’s flag carrier Qantas has survived the pandemic. But its return to normal service – and profitability – is proving to be a bumpy ride. It could well get worse before it gets better.

As domestic and international travel picks up, the airline is struggling to keep up – having laid off thousands of staff whose experience, it turns out, was quite valuable for running such a complex business. Cancelled flights, lost luggage, long delays at airports and low staff morale are pummelling its carefully cultivated reputation.

Qantas engineers took industrial action last month. This week there’s a strike by baggage handlers employed by the contractor used since the airline retrenched almost 2,000 ground crew workers in 2020. (The Fair Work Commission has since ruled this outsourcing was unlawful.)

Former staff have told the ABC’s 4 Corners program they fear the cutbacks will undermine the airline’s safety record.

There is no quick or easy fix. These issues are tied to the airline’s profitability – or lack of it. Last financial year it reported an underlying loss before tax of A$1.89 billion. Since 2020, total losses have been A$7 billion, with the shutdown of travel costing about A$25 billion in revenue, according to chief executive Alan Joyce.

Top Australian Brokers

- Pepperstone - Trading education - Read our review

- IC Markets - Experienced and highly regulated - Read our review

- eToro - Social and copy trading platform - Read our review

A challenging industry

Qantas is by no means alone when it comes to the challenges of rebuilding after COVID. Even in normal times, airlines are notoriously hard businesses to keep in the black.

The products they sell – seats – are highly perishable. Once a flight takes off, any empty seat becomes worthless. It is tempting to fill seats by discounting, but this can lead to competitors doing the same, and create a perception that leads customers to undervalue the product.

There’s a reason so many national carriers are fully or partly government-owned – including Air New Zealand, Emirates, Etihad, Garuda Indonesia, Malaysia Airlines and Singapore Airlines.

It’s debatable how many of these airlines would be viable as standalone commercial operations. An airline regulated by a government with a vested interest in its prosperity may be assisted in a variety of ways, from bailouts and tax subsidies to policies that help protect it from competition on domestic routes.

How to cut costs?

Adding to these difficulties in 2022 are fuel prices, inflated since Russia invaded Ukraine in February. Fuel costs typically account for about a quarter of airline costs.

Hedging contracts have protected Qantas from the full impact of these increases. Like other airlines, it has few options to cut fuel costs besides cutting routes or buying more fuel-efficient aircraft. (It is buying 12 new Airbus planes, but with the plan to offer long-haul flights without stopovers, which will increase fuel consumption.)

So cutting staff costs has become the default option.

Qantas has never shied away from this under Joyce, who was appointed chief executive in 2008.

In 2011 he notoriously grounded the fleet and locked out staff during “hardball” collective bargaining with three unions (the Australian and International Pilots Association, Australian Licenced Aircraft Engineers Association, and Transport Workers Union).

But this combative stance on wages and conditions, and outsourcing so many key activities, has thinned corporate knowledge. Qantas’ problems with lost luggage are clearly linked to sacking so many experienced staff and replacing them with contract workers who don’t necessarily understand how the airline’s complex systems work.

A difficult outlook

It’s easy to look for scapegoats – there are mounting calls for Joyce to go, for example – but there are no easy solutions to the problems Qantas faces.

In the short term it must to balance the cost-cutting required with the reality that further aggravating its workforce will lower customer service – and ultimately its reputation.

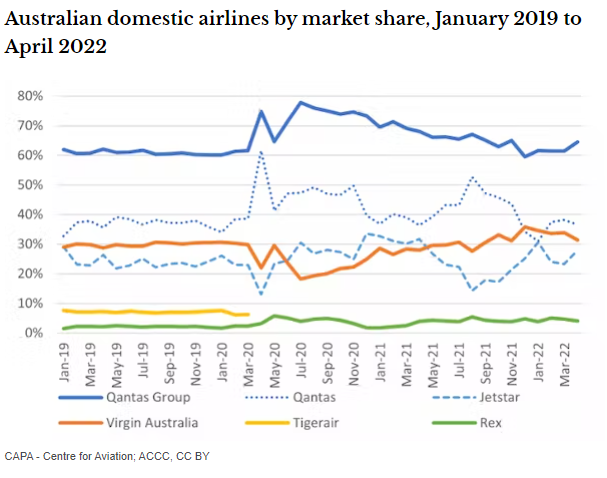

Domestically it has the advantage of its major competitor, Virgin Australia, being in an even worse position. Virgin only survived the pandemic by being sold to US private equity giant Bain Capital. This should save Qantas from a domestic discounting war for the foreseeable future.

But even with subdued domestic competition, the airline industry remains unattractive. For the flying kangaroo, the path back to profitability looks set to be one of many ups and downs.

Originally published by The Conversation

Author: Peter Galvin, Professor of Strategic Management, Edith Cowan University