Australian consumer prices jumped an extraordinary 2.1% in the first three months of the year, the biggest quarterly jump since the introduction of the 10% goods and services tax at the start of the century.

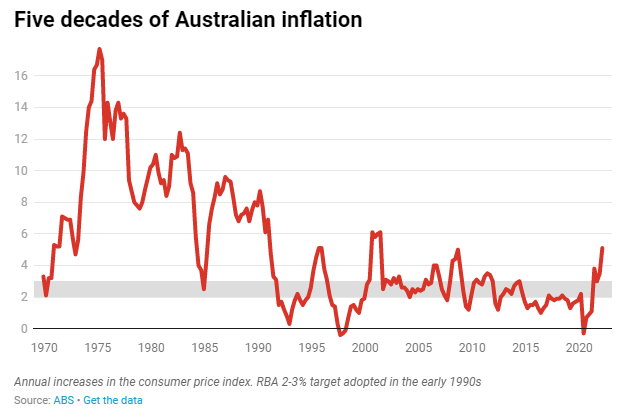

The outsized increase, together with a larger than normal increase in the months to December, pushed Australia’s annual inflation rate way above the Reserve Bank’s 2-3% target to 5.1% – the biggest annual inflation rate for two decades.

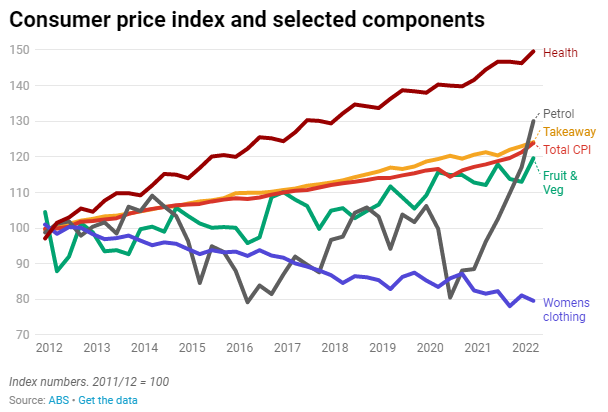

Petrol prices rose to a record high. The Bureau of Statistics says averaged unleaded petrol averaged A$1.83 per litre in the March quarter.

The annual increase, 35.1%, was the biggest since Iraq’s invasion of Kuwait in 1990.

Top Australian Brokers

- Pepperstone - Trading education - Read our review

- IC Markets - Experienced and highly regulated - Read our review

- eToro - Social and copy trading platform - Read our review

New dwelling prices rose due to shortages of labour and materials, and fewer government grants. Fresh food prices have increased due to floods.

Home prices, sometimes erroneously thought to be excluded from the consumer price index, surged 13.7% over the year, the most since the start of the GST.

The increase tracks the cost of buying a new dwelling by an owner occupier, and reflects what the Bureau describes as high levels of building activity combined with ongoing shortages of materials and labour.

While the cost of housing is included in the consumer price index, the cost of land is not, being treated as an investment rather than a consumer good.

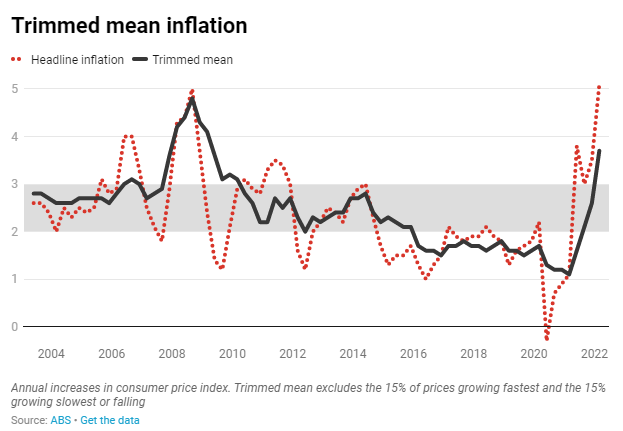

To get a better idea of what would be happening were it not for these unusual and outsized moves, the Bureau of Statistics calculates what it calls a “trimmed mean” measure of underlying inflation.

The trimmed mean excludes the 15% of prices that climbed the most in the quarter and the 15% of prices that climbed the least or fell.

This underlying measure, closely watched by the Reserve Bank, climbed 3.7% – the first time it has climbed beyond the bank’s 2-3% target range since 2010.

Many people don’t believe the official inflation figures. They say they are too low (although interestingly this time, the 5.2% estimate in the Melbourne Institute’s April consumer survey matched reality).

In part this is because people tend to notice the prices that have jumped. Petrol prices are particularly visible. People tend not to notice the many other prices, including rents in some parts of Australia, that have been falling.

And in part it is because movements in the consumer price index are an average.

The price of the bundle of goods and services used by around half the households would have gone up by more than 5.1%, and the price of the bundle used by the other half by less than 5.1%. The households facing the increases notice it more.

Over the past ten years the price of clothing has fallen 6%, and the price of communications services 23%. The price of health services has climbed 40%

Looking ahead, inflation is likely to drop in the June quarter. Oil prices are falling, and the budget petrol price relief will cut prices a further 22 cents a litre.

Some supply chain problems and skilled labour shortages caused by the pandemic are likely to ease. And the Australian dollar has climbed, which should push down the price of imports.

Unless there is a significant pickup in wage growth (we find out in three weeks, three days before the election) inflation may start to come back down of its own accord, without the need for the Reserve Bank to push up rates.

But there are certainly alternative scenarios.

Over to the Reserve Bank

The response of the Reserve Bank to higher prices is not as automatic as often supposed. But with the RBA cash rate at an all-time low, and an increasing risk that the current inflation will become embedded in expectations, an increase in rates is a matter of “when” not “if”.

As Prime Minister John Howard and Treasurer Peter Costello discovered in the election they lost in 2007, the Reserve Bank won’t hold off on increasing interest rates just because an election is imminent.

Asked if the bank would tighten rates if the evidence suggested it needed to near an election, the then governor said: “of course we would, because we do our job”.

After its April meeting the bank said it would wait for information before moving.

over coming months, important additional evidence will be available on both inflation and the evolution of labour costs. Consistent with its announced framework, the board agreed that it would be appropriate to assess this evidence

The labour cost (wage) data are released on May 18, meaning the first increase in interest rates may well not be until after the election, at the board’s June 7 meeting. If the wages data show no acceleration, it might be later.

How high for mortgage interest rates?

The Reserve Bank generally tries to move the “cash rate” (the interest rate on overnight loans) in steps of 0.25 percentage points. But, unusually, the current target is 0.10%. So it might first move 15 points to 0.25%.

If it wants to send a stronger signal, it will move 40 points to 0.50%. Banks are generally not shy about passing these changes on.

If the Reserve Bank hikes more than once, mortgage interest rates might climb from their present range of 3-3.5% to 4-5% over the course of the year.

But the Reserve Bank will not push interest rates as high as it did during previous tightening cycles. Households have more debt, meaning that a rate increase of any given size has more impact than it once would have.

It’s hard to know where a series of rate rises would end, but it’s a fair bet the cash rate will end up higher than the Reserve Bank’s 2-3% inflation target, making the real interest rate positive (above inflation).

Banks are required to assure themselves that borrowers could meet repayments if rates rose by three percentage points, which is just as well.

Who will be hurt?

About a third of households have a mortgage, and face higher payments.

But it will take a while for all of them to be affected. Around 40% of borrowers have “fixed-rate” loans where the interest rate is only adjusted every three years.

And according to the Reserve Bank, typical borrowers are currently two years ahead on repayments, which suggests most will be able to cope.

Originally published by The Conversation

Author: John Hawkins, Senior Lecturer, Canberra School of Politics, Economics and Society and NATSEM, University of Canberra