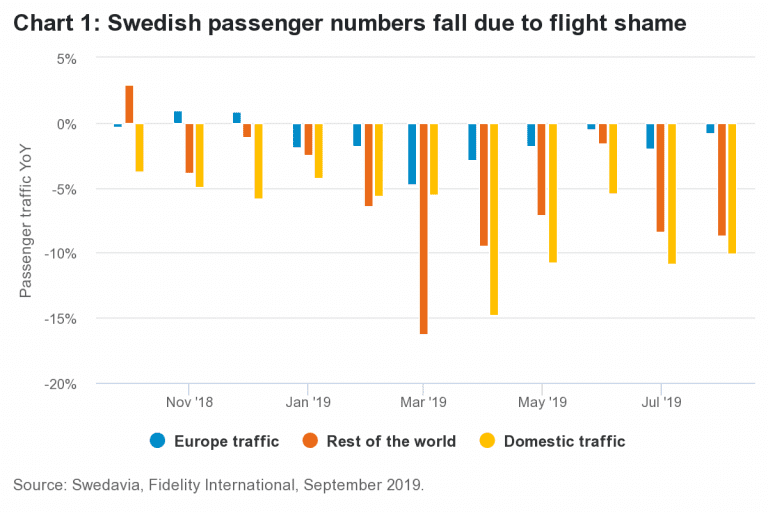

Flight shame, or the guilt travellers feel about the harmful emissions produced by air travel, is starting to reduce passenger numbers in Sweden. If this behaviour spreads to the rest of Europe, and in particular begins to influence corporates to cut down on flights, European airlines face a threat to which there is no obvious solution.

European airlines have had a tough time recently. Rising fuel prices, global growth fears, overcapacity and staff disputes have all played their part in a collective decline of 40 per cent compared with the MSCI Europe since the start of 2018. Partly as a result of the negative sentiment, however, several companies in the sector with good structural growth prospects, such as Wizz Air and IAG, look attractive in valuation terms.

When researching companies, I carefully weigh the impact of long-term secular trends on profits and consider each company through an ESG lens. On this basis, data shows the phenomenon of flight shaming is already starting to reduce passenger numbers in Sweden. But will it catch on elsewhere in Europe and become a bigger issue for the industry as a whole?

What is flight shame?

Top Australian Brokers

- Pepperstone - Trading education - Read our review

- IC Markets - Experienced and highly regulated - Read our review

- eToro - Social and copy trading platform - Read our review

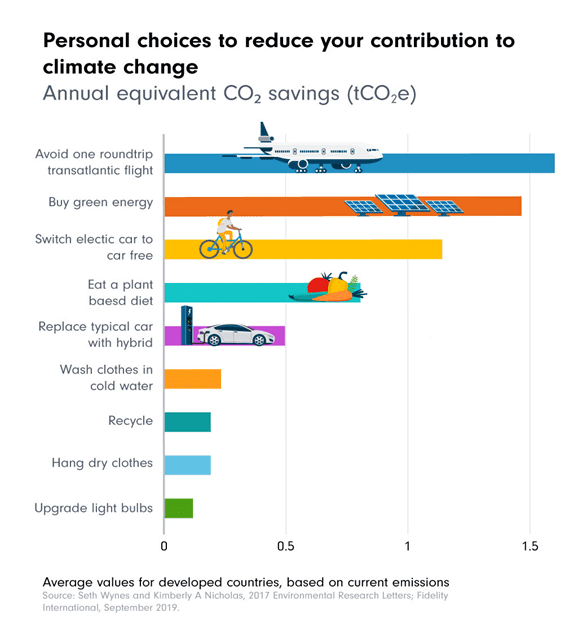

Flight shame is the term used to describe the growing unease some would-be travellers have with the emissions aeroplanes produce that contribute to global warming. It takes the average person eight years’ worth of diligent recycling to reduce CO2 emissions by as much as giving up just one transatlantic roundtrip by plane. The movement has been gaining popularity for several years in Sweden and was propelled further into the limelight this year by the teenage activist Greta Thunberg’s decision to attend the UN Climate Summit in New York by sail boat rather than plane.

In Thunberg’s native Sweden, monthly passenger numbers fell by an average of 3.4 per cent year-on-year between October 2018 and August 2019. Compare this with Germany, which has seen an average monthly increase of 5.2 per cent in the same time, and it’s little wonder Rickard Gustafson, CEO of Scandinavian Airlines, said earlier this year he was convinced flight shame is causing Swedish travellers to think twice about flying

Flight shame still niche

At the moment flight shame garners most enthusiasm in younger travellers. They are more price sensitive and have less money to spend, therefore posing a less significant danger for airlines. But if the sentiment were to spread to corporate travel, a key driver of airline revenues, it would represent a major problem for the industry.

The costs incurred per flight, such as plane leasing, staff costs, fuel, and airport fees are largely fixed no matter how many seats on the aircraft are occupied. This makes airline margins particularly sensitive even to small declines in passenger demand. And while it’s true that demand for air travel is growing rapidly in Asia as disposable incomes rise, long-haul European carriers only receive a low proportion of sales from this market, while regional carriers evidently have no exposure at all.

Regulation is growing

Regulations also appear to be moving in the wrong direction for airlines. Germany recently announced a raft of measures aimed at reducing climate warming, including increasing tax on flights and reducing it on long distance rail journeys. Currently, aviation fuel and intra-Europe plane tickets are not subject to VAT, but this may change given increasing pressure on the European Commission from environmental activists. So far, airlines appear optimistic they can cope with this kind of regulatory change by passing costs on to consumers.

In the past, the airline industry has responded to threats, particularly increased competition, by cutting costs and then lowering prices. But flight shame poses a problem that cannot be solved in the same way. Technology that would greatly reduce harmful emissions, such as electric planes or significant increases in fossil fuel efficiency, is still decades away.

As this is an emerging social trend, it is impossible to predict how far or fast flight shame could spread from Sweden to other European countries. But it is something I am watching closely and plan to commission a private survey in the coming months to further investigate the scope and potential of this phenomenon. The low returns of airlines mean even a small change in attitudes could make life difficult, and there is little they could do about it. For now, I am focused on airlines with strong or improving ESG characteristics, attractive valuations and good structural growth stories that are not under imminent danger should flight shame spread.

Published by Fidelity International investment experts, Fidelity