It is coming up to 18 months since Australia’s Reserve Bank last cut its cash rate.

And what it did then was merely a further cut, from an unprecedented low of 0.25% to a fresh unprecedented low of 0.10%

Since it last changed the direction of rates (started cutting instead of hiking) it has been 10 years and five months.

Which is why it has been telling anyone who asked (and repeatedly using the phrase in its official communications) that it is “prepared to be patient” before changing again. It wants to be sure conditions necessitate such a move.

On Tuesday, in the statement released after the board’s April meeting, the words “prepared to be patient” were missing.

Top Australian Brokers

- Pepperstone - Trading education - Read our review

- IC Markets - Experienced and highly regulated - Read our review

- eToro - Social and copy trading platform - Read our review

The board has literally lost its patience.

Instead of saying it was prepared to be patient “as it monitors how the various factors affecting inflation in Australia evolve”, it said

Over coming months, important additional evidence will be available to the board on both inflation and the evolution of labour costs.

The clear message (and the words in Reserve Bank statements are chosen very carefully) is that if the bank doesn’t like what it sees on inflation and wage costs over the coming few months, it’ll jack up rates, for the first time in a decade.

Prices, and wages

So what is it waiting for?

The first is the March quarter inflation results which will be published by the Australian Bureau of Statistics in three weeks on April 27 during the middle of the election campaign.

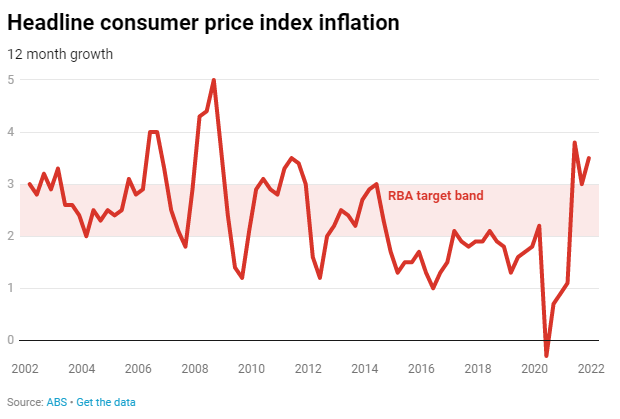

Economists expect headline inflation to be quite high, up from the latest 3.5%

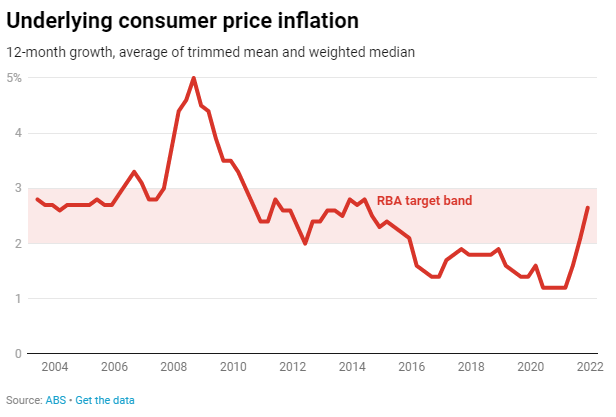

So-called underlying inflation, which filters out unusual price moves, and is what the Reserve Bank actually targets, might not climb as high.

But even if it does, there’s every chance it won’t overly alarm the bank.

This is because the first three months of March were filled with temporary, one-off external shocks to the economy such as the increase in petrol prices and price the impact on supply chains of lockdowns in major Chinese cities.

Conceivably these one-off effects could dissipate after a few months. We were already seeing petrol prices fall before last week’s cut in petrol excise.

Many related price increases might fade away shortly after they arrive, making an increase in rates to restrain prices unnecessary.

For inflation to be sustainably within its 2-3% target band the Reserve Bank says it wants to see an increase in wages growth as well.

Wages are one of the main business costs meaning it is unlikely we will see long-lasting higher price inflation until we have higher wage inflation.

This is why even though the board will have digested the inflation report by its next meeting on May 3 (just ahead of the election) it may well wait until June when it can see the latest wage figures as well.

How high, how soon

If the bank does start raising rates in June, where will it stop?

Market pricing currently predicts the cash rate will jump from 0.10% to 2% by the end of the year, and to more than 3% by next year. They imply an average of one rate hike at every Reserve Bank board meeting for the next 18 months.

This is probably an upper bound for what we can expect. Market economists (the people who advise traders) as opposed to market traders expect the bank to hike no more than a handful of times in the second half of this year.

While jobs growth is strong, with underemployment at its lowest in a decade and unemployment close to its lowest in five decades, the bank will be cautious about slowing the recovery before it delivers widespread higher wage growth.

This raises the question of why interest rates are tipped to remain so low when unemployment is approaching its lowest level in half a century.

It is partly because high household debt means any increase in rates will have a much larger impact on household budgets and spending than it would have.

Interest rates won’t stay close to zero forever. But it will be a long time before they are back to the high levels of 4%+ last seen when the bank began cutting in 2010.

Originally published by The Conversation

Author: Isaac Gross Lecturer in Economics, Monash University