In the heightened tensions of the current geopolitical environment, the debate around sustainable investing has intensified. On the ground, our 2022 ESG Analyst Survey provides signs of how companies are making progress, but much more needs to be done.

Fidelity’s 2022 survey of analysts on sustainability issues comes at a delicate moment. Sustainable investing has grown into a US$35 trillion market, but it faces a series of challenges. Regulators are scrutinising every claim, while the market context has been fundamentally changed by war in Ukraine, declines in both bonds and equities, and the biggest flare-up in inflation in decades.

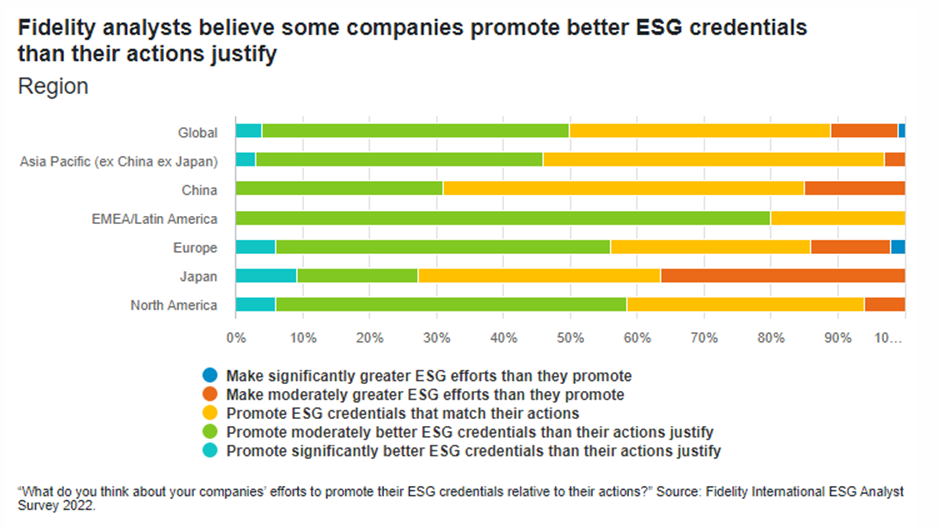

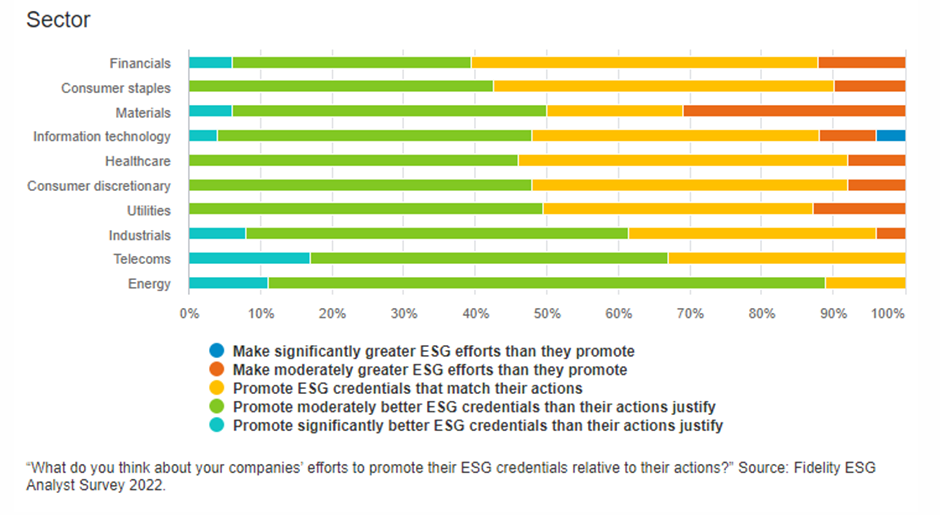

The survey, taking in the views of 161 investment analysts, shows corporates are doing a lot – but there’s still more talk than action. On a positive note, around half our analysts think their companies make ESG efforts that match or exceed what they promote. But that still leaves the other half. Examples where the analysts are concerned include an oil company attracting a lot of attention for its renewable investments although this accounts for only a tiny fraction of the overall business; or a swimming pool services company which mis-labels itself as “water management”. Almost 90 per cent of our energy sector analysts say their companies promote better ESG credentials than their actions justify.

Top Australian Brokers

- Pepperstone - Trading education - Read our review

- IC Markets - Experienced and highly regulated - Read our review

- eToro - Social and copy trading platform - Read our review

However, the gap between aspirations and reality is in itself a sign that companies know what they are supposed to be doing, even if their claims are exaggerated. We know the focus on ESG at companies we invest in is growing. The survey shows 56 per cent of boards now have direct oversight of sustainability, up from 52 per cent last year. Companies are responding to regulatory and investor pressure. The challenge is to help firms set out plans that are ambitious and effective but not out of reach or oversold, and which can then be regularly monitored and updated.

The investment world’s ability to do this is still developing but significant changes are happening. In the survey, our analysts provide detailed accounts of both collaborative and direct one-on-one engagements with companies, where they ask hard questions of senior management based on detailed assessments of their E, S and G plans. Importantly, these are the same financial analysts we have long tasked with watching companies and sectors for investment opportunities: they know these businesses and they know the company managers involved.

Boards now are not just promising to disclose ESG-relevant data, they are hiring departments to count and publish it, just as their accountants publish financial data. This creates baselines from which we all can start to measure in a convincing way whether companies are really making progress. Take net zero carbon targets. The survey shows they look further away for some sectors than a year ago. This reflects the scale of the acceleration necessary but also that we are better equipped to measure the corporate plans to get there.

The scope of activity is broadening, too. A year ago, greenhouse gas emissions and governance dominated conversations with CEOs. This year they and their management teams can answer meaningfully on plastics and deforestation, biodiversity, and water management. US companies, which have trailed behind Europe, are starting to catch up.

There is real complexity, especially around the energy transition. Take an energy company still wedded to coal. Simply dumping the stock lets other investors, uninterested in climate impact, pick up a bargain. Working with the company on its sustainability plan, supporting acquisitions, encouraging it to maintain local industry, to effect change in its suppliers and clients: this is a real transition. Clearer definitions will hopefully drive us closer to making the sophisticated, non-binary choices that the green transition demands.

Change the game

Far from being discouraged, the increased scrutiny and increased corporate focus suggests to me that change is real. It does, however, highlight that there is often a disconnect between the short-term nature of markets and the long-term planning required when dealing with climate change, and making communities more stable and resilient. But the answer is not to give up on trying to use the financial system to bring about change. Rather the system itself must change by adopting agreed global definitions and standards, and by shining a light on the inevitable complexity of transitioning to a greener, more inclusive economy.

Originally published by Fidelity International investment experts